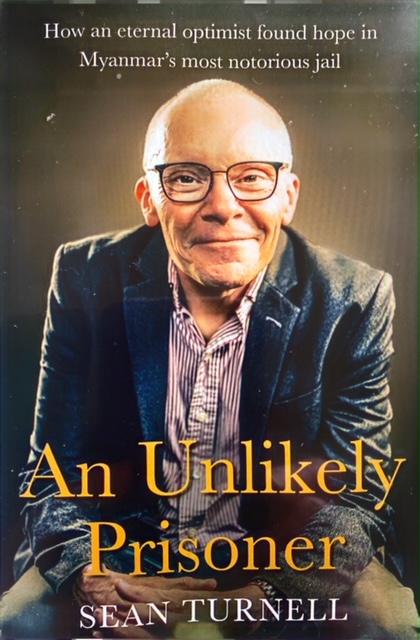

I recently read Sean Turnell’s An unlikely prisoner. If you are asking yourself, ‘Who is Sean Turnell?’, I wouldn’t be at all surprised. Most of our news items these days come and then disappear swiftly as a more enticing morsels (Tay Tay for example) arrive to attract our attention. We have pretty much instantaneous access these days to world, national and local events, so it’s easy enough to put past news out of our minds, to look for the latest happenings. Trouble is, the problems we were introduced to don’t go away, just the media interest. Besides, we are besieged with so much information, it is pretty near impossible to keep abreast of everything.

Sean Turnell, in case you have forgotten, is the Australian economist and academic who spent 659 days locked up in Myanmar’s notorious Insein Prison and Naypidaw Detention Centre, arrested by the military junta which seized control of the country on February 1 2021. The Military, without warning, immediately arrested State Counsellor and de facto head of state, Aung San Suu Kyi, the President Win Myint and other senior figures from the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD). Turnell was taken into custody six days later as he was preparing to leave the country.

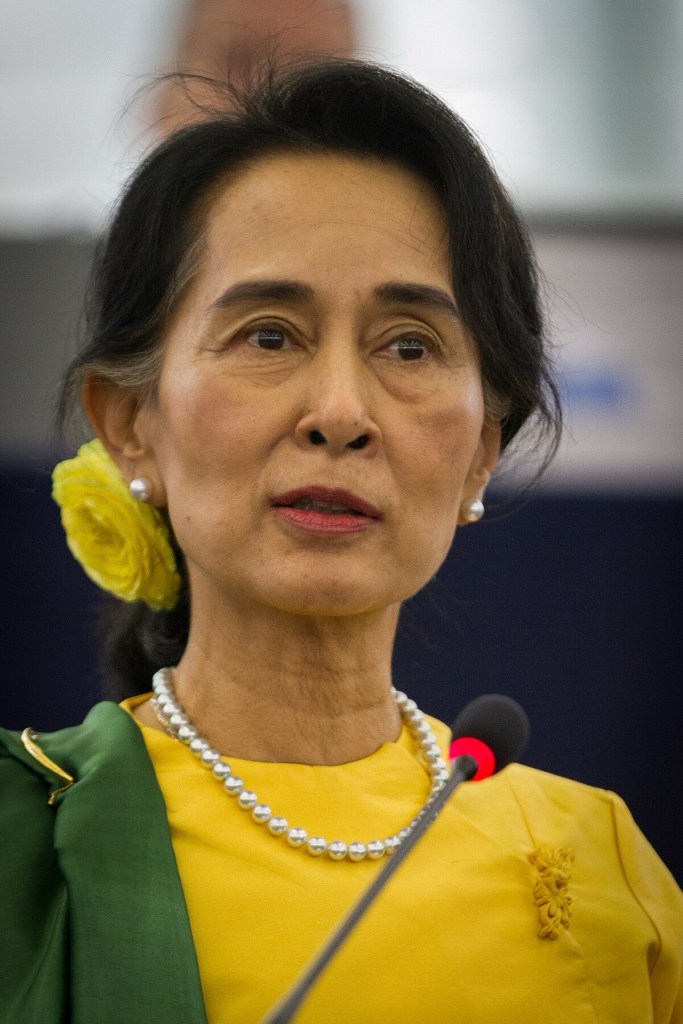

Aung San Suu Kyi , who after years of home detention and great personal sacrifice, had finally managed to become State Counsellor in Myanmar’s democratically elected government in 2016. The expected role of Prime Minister, given she was leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD) parliamentary majority, was not available to her, because of a particular clause in the country’s 2008 constitution vetoing anyone who has parents, spouse or legitimate children or their spouses who owe allegiance to a foreign power. Her two sons are British citizens. The constitution was drawn up by the military junta, which had controlled the country since 1962. Aung San Suu Kyi, her Minister for Planning and Finance, and Deputy Minister for Finance were charged, among other things, with being willing agents of Sean Turnell, who was in turn accused of being a spy. Unlike Sean, they remain incarcerated in Myanmar’s many prisons.

Turnell describes himself as an unlikely prisoner whose idea of an uncomfortable confrontation was having to tell a student that their essay was ‘not really that good’. After a stint at the Reserve Bank, he had joined the staff of Macquarie University in the early 1990s, and shared a house for a time with some members of the Myanmar diaspora. This led to his interest in the country’s politics and economics. In 2009, he wrote a book, Fiery Dragon, which charted Myanmar’s journey from being the richest economy in SE Asia at the start of the twentieth century to the poorest at the beginning of the twenty-first.

When he first visited Myanmar in 2001, Aung San Suu Kyi had just been released from years of house arrest. She invited him to visit her at her family home in Yangon. He says they bonded over a shared interest in Sherlock Holmes and Tolkein. After the NLD landslide election in 2015, The Lady invited him to act as the country’s economic adviser. He was officially employed in 2016 as a special economic consultant to work alongside the country’s economic reformers. He foresaw Myanmar becoming an Asian tiger, just as Vietnam was transforming itself, by boosting international trade and fixing the banking system which he described as little more than a corporate cash box for the country’s oligarchs. He was released as part of general amnesty in November 2022.

It was interesting to read that one of the documents presented at his show trial, charged with violating the Official Secrets Act, was a memo, taken from his own computer, that he had written to Aung San Suu Kyi in 2019. It was presented to the court as having been acquired by Turnell from the Myanmar Government by nefarious means. It outlined ways the NLD’s knowledge of Myanmar’s financial system could be used to sanction members of Myanmar’s military who had engaged in genocidal actions action against the Rohingya in Rakhine State.

When asked by a journalist in an interview since his release, Turnell acknowledged that The Lady did not speak up against the Military at the International Court of Justice in 2019, much to the opprobrium of human rights campaigners. She would, he said “rage against the venality and stupidity” of their actions in private but had to tread much more carefully in public. He recalled that the government was working on a plan for the return of Rohingya refugees at the time, but this was derailed by Covid and the coup d’etat.

Under the guise of a power-sharing arrangement between the military and civil society, the 2008 Constitution guarantees that 25% of seats in the Parliament of Myanmar are reserved for the Military, as are the Ministries of Defence, Home Affairs and Border Affairs.

The Constitution is hard to amend. This requires more than 75% of the Parliament to approve any change, which effectively gives veto power to the armed forces – the Tatmadaw. In addition, a state of emergency can be declared if there is sufficient reason for the union’s disintegration by insurgency, violence and forcible means. This will result in the derogation of civil rights and the transfer of executive, legislative and judicial power from the Union to the Commander-in-chief of defence services. The Military claimed voter fraud in the general elections of November 2020, which the NLD again won in a landslide and whose results were widely seen as credible. They declared a state of emergency.

All of this was certainly reason to tread carefully.

In the same interview, Sean Turnell said:

‘With Suu Kyi locked away, it’s like a curtain went down and no one’s thought about it since’. She is now 78 years of age. The Military, he says, are just waiting for her to die.